INDUS VALLEY CIVILISATION

Introduction:

- The Indus Valley Civilization (IVC) was a Bronze Age civilization (3300–1300 BCE; mature period 2600–1900 BCE).

- The Indus Valley Civilization is also known as the Harappan Civilization, after Harappa, the first of its sites to be excavated in the 1920s on the banks of a dried up bed of the Ravi river, an Indus tributary (now in Pakistan, Punjab).

- The discovery of Harappa, and soon afterwards, Mohenjo-Daro (on the bank of Indus River), was the culmination of work beginning in 1861 with the founding of the Archaeological Survey of India in the British Raj.

- Along with Ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia, it was one of three early civilizations and the most widespread among them, covering more than 1.25 million sq. km.

- Inhabitants of the ancient Indus river valley developed new techniques in handicraft (carnelian products, seal carving) and metallurgy (copper, bronze, lead, and tin). The Indus cities are noted for their urban planning, baked brick houses, elaborate drainage systems, water supply systems, and clusters of large non-residential buildings.

Background and Origin:

- The Indus civilization had indigenous roots and that its cultural precursors were the chalcolithic cultures of the northwest that flourished in the fourth and third millennia BC. Contrary to the views of some early scholars, Indus cities were not created either through the dissemination of the idea of civilization or by migration of population groups from West Asia.

- Indus settlements mainly flourished in the part of the Indian subcontinent, which lies west of the Delhi-Aravalli-Cambay geographical axis. Several segments of that zone had seen the birth and development of agricultural communities, between 7000 BC and the genesis of urban centres in the first part of the third millennium BC. The subsistence pattern that is widely seen at Harappan sites – a combination of wheat and barley cultivation and domesticated animals in which cattle was most preferred – goes back to Mehrgarh in the Kachhi plain of Baluchistan which has also yielded the earliest evidence of agricultural life in South Asia (7000 BC).

- From the 5th millennium BC onwards, this pattern is found spread all over the major areas of Baluchistan, from the Zhob-Loralai region in the northeast to Las Bela towards the south.

- At the same time, a majority of classic Indus sites are in riverine lowlands and the manner in which settlements and subsistence patterns had evolved in those areas, over a span of more than a thousand years prior to the efflorescence of the Harappan civilization, is central to understanding its evolution. In several lowland areas, there was a long period of antecedence.

Hakra ware culture:

- At the beginning of the fourth millennium BC, the Cholistan tract saw a phase of occupation, known as the ‘Hakra ware’ culture, named after the river around which its distinctive ceramic assemblage was first discovered. Although the largest concentration of sites is around the Hakra river, its spread included Jalipur in Multan and Kunal in Haryana. Most of the sites seem to be small camps with a few permanently established settlements (such as Lathwala in Cholistan).

- The Hakra horizon is the first culture of the lowlands, which utilized both the desert and the riverine environments, using a variety of stone and copper tools. There are also occasional manufactured goods in raw materials that were not locally available.

- Rakhigarhi has thick deposits of ‘Hakra Ware’. Hakra people here are considered to be the earliest Indus inhabitants.

Amri culture:

- Towards the western fringe of the Indus lowlands, the fourth millennium BCwitnessed the birth of another culture, known as the Amri culture (after the site of Amri) which dominated the Kirthar piedmont (in Baluchistan and lower Sindh) andKohistan. Some Amri sites are marked by an ‘lower town’ division, a settlement plan that can be witnessed subsequently, in a highly developed and sophisticated form, in the layout of Indus cites.

- Amri has multi-level small occupation and it was fortified town. Later on more and more elements of the Indus Valley culture appear and finally it became Indus Valley Site. Amri is close to Balochistan where development of earlier farming communities from 6000BC to 4000BC ultimately led to urbanization.

Kot Diji culture:

- The ancient site at Kot Diji was the forerunner of the Indus Civilization. The occupation of this site is attested already at 3300 BCE. The remains consist of two parts; the citadel area on high ground (about 12 m), and outer area.

- The use of mud bricks in the Indus ratio of 1:2:4, along with a drainage systembased on soakage pits are found.

- The interesting find at Kot Diji is a toy cart, which shows that potter’s wheel lead to wheels for bullock carts.

- There is also an extensive but partly standardized repertoire of ceramic designs and forms (some of which are carried over into the Indus civilization), crafts and asophisticated metallurgy that includes the manufacture of silver jewels and disc-shaped gold beads (typical of the Indus civilization), wide transport and exchange of raw materials, square stamp seals with designs, the presence of at least two signs of Indus writing at Padri and Dholavira (both in Gujarat) and ritual beliefs embodied in a range of terracotta cattle and female figurines.

- The term ‘early Harappan’ is appropriate for this phase since a number of features related to the mature Harappan period (a designation used for the classic urban,civilizational form) are already present. Several of these features also evoke the presence of commercial and other elite social groups.

- When one considers the intensification of craft specialization, dependent on extensive networks through which the required raw materials were procured, or the necessity of irrigation for agriculture in the Indus flood plain, without the risk of crop failure, for which a degree of planning and management was essential, theemergence and the character of the controlling or ruling elites becomes clear.

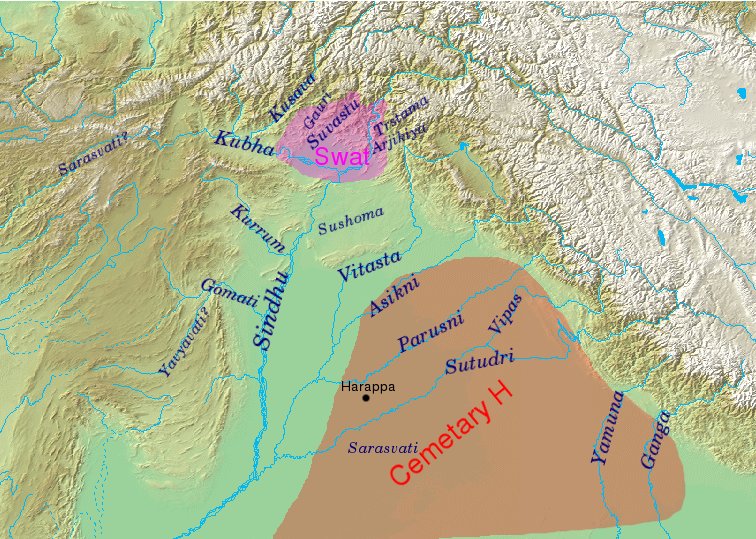

Geography of IVC:

- The Indus Valley Civilization encompassed most of Pakistan and parts of northwestern India, Afghanistan and Iran, extending from Balochistan in the west to Uttar Pradesh in the east, northeastern Afghanistan to the north andMaharashtra to the south.

- The geography of the Indus Valley put the civilizations that arose there in a highly similar situation to those in Egypt and Peru, with rich agricultural lands being surrounded by highlands, desert, and ocean.

- It flourished in the basins of the Indus River and the now dried up Sarasvati River, which once coursed through northwest India and eastern Pakistan together with its tributaries flowed along a channel, presently identified as that of the Ghaggar-Hakra River.

- The course of the Indus river in the third millennium BC was more southeasterlyand it flowed into the Arabian sea in the vicinity of the Rann of Kutch.

- Coastal settlements extended from Sutkagan Dor in Western Baluchistan to Lothalin Gujarat.

Lower Indus basin:

- In the lower Indus basin, Mohenjodaro dominated the flood plain, agriculturally the richest part of Sind. Lower Indus basin is also marked by lake depressions, such as the Manchhar, where fishing settlements existed.

- Towards the west, there were clusters of sites in the foothills of the Kirthar mountain range and the Kohistan. There, agriculture must have depended on spring water and rains. Routes linking up with Baluchistan also passed through this area.

Upper Sind and Baluchistan:

- In upper Sind, the Sukkur-Rorhi hills saw settlements of workmen in and around flint quarries, the raw material from which Harappan blades were manufactured.As one moves west, Baluchistan is reached where Harappan settlements are foundin a variety of terrain– across the northern mountain rim, on the flat Kacchi plain,towards the south and along the coastal area known as the Makran. In Makran, the fortified sites of Sutkagendor and Sotka-koh were important in terms of the Indus civilization’s sea trade with the Persian Gulf and Mesopotamia. From these points,convenient routes linked up with the interior.

- In other parts of Baluchistan, Indus sites are found in areas that are still agriculturally viable and lie on arterial routes. Pathani Damb, for instance, was near the Mula pass, from where a route went across the Kirthar range while Naushahrowas in the general vicinity of the Bolan, through which a major route led to Afghanistan. Such routes were important because through them, Baluchistan’s metalliferrous ores (copper and lead) and semi-precious stone (lapis lazuli and turquoise) could be procured by the resource-poor Indus valley.

- The northernmost site of the Indus civilization, Shortughai, (on the Oxus River) is in northeast Afghanistan. Shortughai provided access to Badakshan’s lapis lazuli and possibly to the tin and gold resources of Central Asia.

Northeast of Sind:

- To the northeast of Sind is the Pakistan province of Punjab. A large part of the province is comprised of doabs or tracts lying between two rivers. Of these, the Baridoab (or land between the Ravi and an old bed of the Beas) sites has the sprawling city of Harappa.

South of the Sutlej:

- South of the Sutlej river, is Bahawalpur. Part of it is made up of the desert trace ofCholistan, through which the Hakra river flowed. The largest cluster of Indus settlements is found here. Geographically, this tract connects the Indus plains with Rajasthan, which was vast copper deposits. There were several exclusive, industrial sites in Cholistan, marked by kilns, devoted to large-scale craft production that included the melting and smelting of copper.

East of the Sutlej and Ghaggar-Hakra beds :

- East of the Sutlej is the alluvial terrain of the Indo-Gangetic divide, a transitional area between the Indus and the Ganga river systems, made up of the Indian states of Punjab, Haryana, Delhi and Ghaggar river course in Rajasthan.

- A large part of the riverine and stream drainage from the Siwalik ridge between the Sutlej and Yamuna used to converge into the Ghaggar, the Indian name for the river known as the Hakra in Pakistan. There were several provincial urban centresin this region such as Kalibangan and Banawali although Rakhigarhi (in the Hissar district of Haryana) was the largest city.

- Sites along the Ghaggar-Hakra beds are: Rupar, Rakhigarhi (Largest Harappan Site), Sothi, Kalibangan, Bhiranna (Oldest Harappan Site), Ganwariwala

Rann of Kutch, Gulf of Cambay and Kathiawad:

- Finally, the spread of the Indus civilization included the quadrilateral of roughly119,000 square kilometers between the Rann of Kutch and the Gulf of Cambay.Dholavira was the city of the Rann, with its vast expanse of tidal mud flats.

- Further east, Kathiawad, now known as Saurashtra, is formed of Deccan lava and on its eastern edge flourished the port town of Lothal.

- The mainland of Gujarat is alluvial, formed by the Sabarmati, Mahi and minor parallel streams, actively prograding into the Gulf of Cambay. Here, Bhagatrav, on the estuary of the Kim river, forms Gujarat’s southernmost extension of the Indus civilization.

Others:

- An Indus Valley site has been found in the Gomal River valley in northwestern Pakistan, at Manda, Jammu on the Beas River near Jammu, India, and atAlamgirpur on the Hindon River, only 28 km from Delhi.

- Indus Valley sites have been found most often on rivers, but also on the ancient seacoast,for example, Balakot, and on islands, for example, Dholavira.

Why not Indus-Saraswati civilization?

- According to some archaeologists, more than 500 Harappan sites have been discovered along the dried up river beds of the Ghaggar-Hakra River and its tributaries, in contrast to only about 100 along the Indus and its tributaries; consequently, in their opinion, the appellation Indus Ghaggar-Hakra civilization orIndus-Saraswati civilization is justified.

- However, these arguments are disputed by other archaeologists who state that the Ghaggar-Hakra desert area has been left untouched by settlements and agriculture since the end of the Indus period and hence shows more sites than found in the alluvium of the Indus valley. Chances of survival of sites on desert areas were more.

- Also the number of Harappan sites along the Ghaggar-Hakra river beds have been exaggerated and that the Ghaggar-Hakra, when it existed, was a tributary of the Indus, so the new nomenclature is redundant.

Early Excavations:

- In 1856, General Alexander Cunningham, later director general of the archaeological survey of northern India, visited Harappa where the British engineers John and William Brunton were laying the East Indian Railway Company line connecting the cities of Karachi and Lahore. They were told of an ancient ruined city near the lines. Visiting the city, he found it full of hard well-burnt bricks. Bricks, which had already been used by villagers in the nearby village of Harappa, were now provided ballast along the railroad track.

- In 1872–75 Alexander Cunningham published the first Harappan seal (with an erroneous identification as Brahmi letters). It was half a century later, in 1912, that more Harappan seals were discovered, prompting an excavation campaign under Sir John Marshall in 1921–22 and resulting in the discovery of the civilization at Harappa by Sir John Marshall, Rai Bahadur Daya Ram Sahni and Madho Sarup Vats, and at Mohenjo-daro by Rakhal Das Banerjee, MacKay, and Sir John Marshall.

| NAME OF SITES | YEAR OF EXCAVATION | EXCAVATORS | REGION/RIVER | FEATURES |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Harappa | 1921 | Daya Ram Sahni | Montgomery district of Punjab (Now in Pak) on the left bank of Ravi |

|

| Mohenjo-daro | 1922 | R.D.Banarjee | Larkana district in Sind on the right bank of Indus(Now in Pak) |

|

| Chanhu-daro | 1931 | N. Gopal Majumdar, Mackey | Situtated in Sind on the bank of Indus |

|

| Kalibangan | 1953 | A. Ghosh | Situated in Rajasthan on the Bank of Ghaggar |

|

| Lothal | 1953 | S.R. Rao | Situated in Gujarat on Bhogava river near Gulf of Cambay |

|

| Banwali | 1974 | R.S. Bisht | Situated in Hissar district of Haryana |

|

| Surkotada | 1964 | J.P. Joshi | Situated inKutch (Bhuj) district of Gujarat |

|

| Sutkagendor | 1927 | Stein, R.L. | Situated in Baluchistan on Dast River |

|

| Amri | 1935 | N.G. Majumdar | Situated inSind on the bank of Indus |

|

| Dholavira | 1985-90 | R.S. Bisht | Situated in Gujarat inRann of Kutch |

|

| Rangpur | 1953 | M.S. Vats, B.B. Lal & S.R. Rao | Situated on the bank ofMahar in Gujarat |

|

| Kot Diji | 1953 | Fazal Ahmed | Situated on the bank ofIndus |

|

| Ropar | 1953 | Y.D. Sharma | Situated in Punjab of the banks ofSutlej |

|

| Balakot | 1963-76 | George F Dales | Situated on the Arabian Sea |

|

| Alamgirpur | 1958 | Y.D. Sharma | Situated onHindon in Ghaziabad |

|

Note: To know more abut individual sites in detail, visit HISTORY THROUGH MAP

Character of the Indus civilization:

- The Indus civilization, while sharing many general features with the contemporaryBronze Age cultures such as the Sumerian civilization of Mesopotamia and Old Kingdom Egypt, had its own distinct identity.

- The Indus phenomenon is called a civilization because it incorporated within itself the social configurations and organizational devices that characterize such a cultural form.

- It was the only literate subcontinental segment of its time. More than 4000 Indus inscriptions have been found, and even though they remain undeciphered, the script was used for mercantile purposes (as suggested by the seals and sealings),personal identification (in the form of shallow inscriptions on bangles, bronze implements etc.) and possibly for civic purposes (underlined by the remains of a massive inscribed board at Dholavira).

- The civilization’s essence was a settlement pattern in which cities and towns were prominent. That such urban centres contained monumental structures whose construction required large outlays of labour and resources, and were marked byheterogeneous economic activities, are other indicators of civilization.

- Earlier, Mohenjodaro and Harappa had alone stood out as the civilization’s large cities, today we know of many more whose dimensions qualify them for a similar status. These are fairly spread out – Ganweriwala in Cholisatan, Dholavira in Kutch and Rakhigarhi in Haryana are such centres.

- The largest variety and quantity of jewellery, statuary and seals, are found in urban centres and indicate that craft production was geared to the demands of city dwellers.

- Further, the characters of planning, the necessity of written transactions, and the existence of a settlement hierarchy in which urban and rural settlements of various sizes and types were functionally connected indicate administrative organization on a scale that was unprecedented in relation to other protohistoric subcontinental cultures. Many of these are archaeological indicators of a state society as well. Whether there were several states or a unified empire in Harappan times remains unclear. Urban settlements may have functioned as city-states since their layout and character suggests the presence of local aristocracies, merchants and craftspeople.

- For one thing, with a geographical spread of more than a million square kilometers, this was the largest urban culture of its time. Unlike Mesopotamia and Egypt, there were no grand religious shrines nor were magnificent palaces and funerary complexes constructed for the rulers. Instead, its hallmark was a system of civic amenities for its citizens rarely seen in other parts of the then civilized world – roomy houses with bathrooms, a network of serviceable roads and lanes, an elaborate system of drainage and a unique water supply system.

- Dholavira’s network of dams, water reservoirs and underground drains andMohenjodaro’s cylindrical wells, one for every third house, epitomize the degree of comfort that townspeople enjoyed in relation to contemporary Mesopotamians and Egyptians who had to make do with fetching water, bucket by bucket, from the nearby rivers.

Chronology:

- It is unlikely that civilizational efflorescence was a simultaneous process in all parts of the Harappan distribution area.

- It matured first in lower Sind, Cholistan and the Kutch region, which was linked by a river to the Cholistan area. Cities like Harappa, Kalibangan and Banawali came up a little later.

- The end was also staggered in time. Urban decline at Mohenjodaro had set by 2200 BC and by 2100 BC, it had ceased to exist as a city. However, the civilization continued after 2000 BC in other areas and at some sites survived till later.

- The Early Harappan, Mature Harappan, and Late Harappan phases are also called the Regionalisation, Integration, and Localisation eras, respectively, with the Regionalization era reaching back to the Neolithic Mehrgarh II period.

- Late Harappan has H type Cemetery and Ochre Coloured Pottery

Early Harappan (3300 BCE- 2600 BCE):

| 3300–2800 | Harappan 1 (Ravi Phase) named after the nearby Ravi River |

| 2800–2600 | Harappan 2 (Kot Diji Phase, Nausharo I, Mehrgarh VII) |

- The Early Harappan is related to the Hakra Phase, identified in the Ghaggar-Hakra River Valley and coincides the Kot Diji Phase (2800–2600 BCE, Harappan 2), named after a site in northern Sindh, Pakistan, near Mohenjo Daro.

- The earliest examples of the Indus script dated to 3rd millennium BC. Discoveries from Bhirana indicate that Hakra ware from this area dates from as early as 7500 BC.

- The mature phase of earlier village cultures is represented by Rehman Dheri andAmri in Pakistan.

- Kot Diji represents the phase leading up to Mature Harappan, with the citadel representing centralised authority and an increasingly urban quality of life.

- Another town of this stage was found at Kalibangan in India on the Hakra River.

- Trade networks linked this culture with related regional cultures and distant sources of raw materials, including lapis lazuli and other materials for bead-making. Villagers had, by this time, domesticated numerous crops, including peas, sesame seeds, dates, and cotton, as well as animals, including the water buffalo.

- Early Harappan communities turned to large urban centres by 2600 BCE, from where the mature Harappan phase started.

Mature Harappan:

| 2600–1900 | Mature Harappan (Indus Valley Civilization) | Integration Era |

| 2600–2450 | Harappan 3A (Nausharo II) | |

| 2450–2200 | Harappan 3B | |

| 2200–1900 | Harappan 3C |

- By 2600 BCE, the Early Harappan communities had been turned into large urban centres. Such urban centres include Harappa, Ganeriwala, Mohenjo-Daro in Pakistan, and Dholavira, Kalibangan, Rakhigarhi, Rupar, and Lothal in India.

Cities:

- A sophisticated and technologically advanced urban culture is evident in the Indus Valley Civilization making them the first urban centres in the region. The quality of municipal town planning suggests the knowledge of urban planning and efficient municipal governments which placed a high priority on hygiene, or, alternatively, accessibility to the means of religious ritual.

- The Harappan City was divided into the upper town called the Citadel and the lower town.

- Lower Town was the residential area where the common people lived.

Citadel:

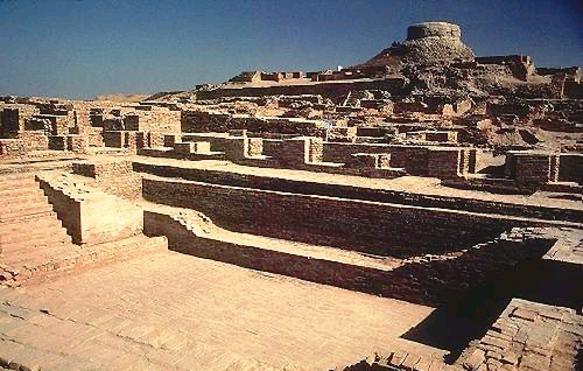

- The existence of a theocratic and authoritarian society indicated by the presence of large and well-fortified citadels in each of the capital cities. These citadels always face west which served as sanctuaries for the cities` populations in times of attack and as community centers in times of peace. The citadel at Harappa measuring 1400 ft. x 600 ft. on mound 40 ft. high which faced foundation with brick embankment 45 ft. thick. The citadel at Mahenjo-daro included a very large building that may have been a palace.

- The purpose of the citadel remains debated. In sharp contrast to this civilization’s contemporaries, Mesopotamia and Ancient Egypt, no large monumental structures were built. There is no conclusive evidence of palaces or temples—or of kings, armies, or priests. Some structures are thought to have been granaries.Although the citadels were walled, it is far from clear that these structures were defensive. They may have been built to divert flood water

Houses:

- Houses and other buildings were made of sun-dried or kiln-fired mud brick.Houses opened only to inner courtyards and smaller lanes. The house-building in some villages in the region still resembles in some respects the house-building of the Harappans.

- Generally house had an indoor and outdoor kitchen. The outdoor kitchen would be used when it was warmer (so that the oven wouldn’t heat up the house), and the indoor kitchen for use when it was colder. In present day, village houses in this region (e.g. in Kachchh) still have two kitchens.

City Wall:

- Each city in the Indus Valley was surrounded by massive walls and gateways. The walls were built to control trade, military invasion and also to stop the city from being flooded.

- Each part of the city was made up of walled sections. Each section included different buildings such as: Public buildings, houses, markets, craft workshops, etc.

Streets:

- The Harappans were excellent city planners. They based their city streets on a grid system. Streets were oriented east to west. The roads and streets intersected at right angles. There were covered drains along the road. Houses were built on either side of the roads and streets.

- Each street had a well organized drain system. If the drains were not cleaned, the water ran into the houses and silt built up. Then the Harappans would build another storey on top of it. This raised the level of the city over the years.

- The advanced architecture of the Harappans is shown by their impressivedockyards, granaries, warehouses, brick platforms, and protective walls.

Granaries:

- The granary was the largest structure in Mohenjodaro, in Harappa there were about six granaries or storehouses. These were used for storing grain. Large granaries were located near each of the citadels, which suggest that the state stored grain for ceremonial purposes and possibly the regulation of grain production and sale.

“Granary,” Harappa (Two rows of six rooms)

Settlement pattern:

- The settlement pattern was a multi-tiered one with urban and rural sites that were markedly varied in terms of size and function.

- There were cities of monumental dimensions like Mohenjodaro,Harappa, Dholavira and Rakhigarhi that stand out on account of their size (more than 100 hectares each) and the character of their excavated remains.

- There is impressive evidence of centralized planning. City space was divided into public and residential sectors. At Harappa and Mohenjodaro, the separation of the largely public administrative sector from the residential part of the city took the form of two separate mounds.

- Dholavira’s city plan was more intricate. At its fully developed stage, it had three parts made up of the citadel which was divided into a ‘castle’ and a ‘bailey’ area, the idle town and the lower town, all interlinked and within an elaborate system of fortification.

- Mohenjodaro’s citadel was constructed on a gigantic artificial platform (400 x 100m) made of a mud brick retaining wall enclosing a filling of sand and silt. This platform, after being enlarged twice, attained a final height of 7 metres and provided a foundation on which further platforms were built in order to elevate important structures such as the Great Bath and the granary, so that the highest buildings were about 20 metres above the surrounding plains.

- The intermediate tier of the urban hierarchy was made up of sites that in several features like the layout of the monumental cities of the civilization but are smaller in size. Kalibangan, Lothal, Kot Diji, Banawali and Amri are some of them and they can be considered as provincial centres.

- Kalibangan, like Mohenjodaro and Harappa, comprised of two fortified mounds – the smaller western one contained several mud brick platforms with fire altars on one of them. Most of the houses on the estern mound had fire-altars of a similar type.

- Lothal was also a fortified town with its entire eastern sector being taken up by adockyard (219x13m in size) which was connected with the river through an inlet channel. In its vicinity was the ‘acropolis’ where the remains of a storehouse, in which clay sealings were discovered. Lothal’s urban morphology also suggests that there is no necessary relationship between the size of a city and its overall planning. Mohenjodaro was at least 25 times the size of Lothal but the latter shares with it the presence of two separate areas, burnt brick houses, and regularly aligned streets and drains. In fact, it paved streets and lanes are unrivalled in the Indus context.

- The third tier of the Indus settlement hierarchy is made up of small, urban sites. These show some evidence of planning but no internal sub-divisions. Notwithstanding their size and structurally unprepossessing character, they had urban functions. Allahadino in Sind is one such site,which had a diameter of only 100 metres but was an important metal crafting centre. Similarly, Kuntasi in Gujarat is a small Harappan fortified settlement where semi-precious stones and copper were processed.

- Urban centres were supported by and functionally connected with rural hinterlands of sedentary villages and temporary / semi-nomadic settlements. While the latter are generally small with thin occupational deposits, in the case of villages, outlines of huts and relatively thick deposits have been encountered. Kanewal in Gujarat was a village settlement. Similarly, the archaeological deposits of the Harappan phase in the Yamuna-Ganga doab – at Alamgirpur and at Hulas – indicates that the pioneer colonizers of that area lived there for a long period of time. On the basis of size, it is not wise to distinguish rural and urban sites of the Indus civilization. InCholistan, there are a few large sites, one of which covers 25 hectares (and, thus, is large than Kalibangan), which have been described as nomadic settlements, not urban ones. On the other hand, Kuntasi was only 2 hectares in size but has been rightly classified as an urban settlement because of its functional role as a provider of craft objects.

Water Management System:

- As seen in Harappa, Mohenjo-Daro and the recently partially excavated Rakhigarhi, this urban plan included the world’s first known urban sanitation systems.

- IVC contain the world’s earliest known system of flush toilets. These existed in many homes, and were connected to a common sewerage pipe.

- The ancient Indus systems of sewerage and drainage that were developed and used in cities throughout the Indus region were far more advanced than any found in contemporary urban sites in the Middle East

- Within the city, individual homes or groups of homes obtained water from wells. From a room that appears to have been set aside for bathing, waste water was directed to covered drains, which lined the major streets.

- Found at Mohenjodaro is an enormous well-built bath (the “Great Bath”), which may have been a public bath. The Great Bath might be the first of its kind in the pre-historic period. This ancient town had more than 700 wells, and most houses in Mohenjo-daro had one private well.

- Lothal was a port at the Arabian Sea with a dockyard.

- Dholavira’s system of water management was architectural marvel which was crucial in an area, which is prone to frequent droughts. Rain water in the catchment areas of the two seasonal streams – Manhar and Mansar – was dammed and diverted to the large reservoirs within the city walls. Apparently, there were 16 water reservoirs within the city walls, covering as much as 36 percent of the walled area. Brick masonry walls protected them, although reservoirs were also made by cutting into the bedrock. Furthermore, drains in the ‘castle-bailey’ area carried rainwater to a receptacle for later use.

- Dholavira had a series of water storing tanks and step wells, and it had at least five baths, size of one is comparable with the Great Bath of Mohenjo-daro.

Authority and governance:

- Archaeological records provide no immediate answers for a center of power or for depictions of people in power in Harappan society. But, there are indications of complex decisions being taken and implemented. For instance, the extraordinary uniformity of Harappan artifacts as evident in pottery, seals, weights and bricks. These are the major theories:

- There was a single state, given the similarity in artifacts, the evidence for planned settlements, the standardised ratio of brick size, and the establishment of settlements near sources of raw material.

- There was no single ruler but several: Mohenjo-daro had a separate ruler, Harappa another, and so forth.

- Harappan society had no rulers, and everybody enjoyed equal status.

Burial In IVC:

- There are over fifty-five burial sites in the Indus valley were found. The principal sites are Harappa Kalibangan, Rakhigarhi, Lothal, Rojdi, and Ropar. The burials are interpreted primarily as reflections of social structure and hierarchy. The strongest evidence for this interpretation would be burial sites in Harappa, cemetery R-37 and Cemetery H.

- R-37 is the smaller site compared to cemetery H, and has about 200 burials. The strong genetic affinities among female population in the R-37 cemetery prove that it was a restricted cemetery that was used by a particular group or family that lived in Harappa. These genetic affinities that are exhibited in the female population also show that the Harappan people practiced natural locality, a system in which the newly wed couple moved to live with the woman’s side of the family. Therefore clearly the R-37 cemetery proves that individuals of high class and status in a society were treated very differently and had a separate burial site.

- In general, the burials in the Harappan period were all in brick or stone lined rectangular or oval pits. The body was usually interred clothed shrouded or in a wooden coffin in the north south direction in a straight direction. The bodies of the individuals were usually buried with their jewelry which usually consisted of bangles made from shell, steatite beads, etc, and the men usually wore earrings. Copper mirrors have been found only amongst the bodies of the females which show a specificity of grave goods by gender.

- The burials at Kalibangan, the other large burial site are of three types.

- Type 1 – the bodies were buried in a supine position similar to R-37 with skeletal remains.

- Type 2 – pot burials in circular pits. The pot burials are an interesting and rare type of burial in which the bodies of the individual are crammed into pots and buried.

- Type 3 – Large pots which were found interred in rectangular or circular pits with no skeletal remains.The most important individual in the cemetery is an older male. He was interred in a old brick chamber with 70 pottery vessels. The man was also decked in jewelry of expensive nature. Clearly this individual is of high importance in the society. On average an individual has 0 to 40 pottery vessels interred as grave goods, but the individual who had 70 pots was clearly outranked others in the cemetery proving that the Harappan civilization was a society which gave a lot of importance to hierarchy and status

- In Ropar a man was found buried with a dog. In Rodji two infants were found buried beneath the floor of a house. In Lothal three multiple burials have been found. This could possibly be the practice of sati but it is doubtful. The unique burials in this site show that not all burials were solely centered on social hierarchy and status.

- Mohenjo daro is one of the biggest cities excavated in this civilization but it has no cemeteries. But there were a few bodies that were found scattered throughout the city in disarray. The skeletons seem to be in a state of trauma and it was as if they had been buried in a state of action with weapons in their hand. The causes of these burials have been hypothesized due to loss of civic rules and order in the city or an invasion of some kind.

Subsistence:

- A stable system of agriculture, supplemented by animal husbandry, hunting andplant gathering, provided economic sustenance to urban networks.

- In view of the widely differing ecological conditions of the distribution area of this civilization, the subsistence strategy is not likely to have been a single or uniform one.

- The Harappans were familiar with the plough. Terracotta ploughs have been found at Indus sites in Cholistan and at Banawali and a ploughed field was revealed through excavation at Kalibangan. Though it belonged to the early Harappan period, there is no reason to doubt that the pattern continued during the mature Harappan period. The Kalibangan field contained two sets of furrows crossing each other at right angles, thus forming a grid pattern, and it is likely that two cropswere raised in the same field. In modern fields in that zone, mustard is grown in one set of furrows and horse gram in the other.

- Mixed cropping is suggested by other evidence as well as, for instance, in the mixture of wheat and barley at Indus sites. Such mixed cropping is practiced even today in many parts of north India as an insurance against weather hazards so that wheat fails to ripen, the hardier barley is sure to yield a crop.

- Earlier, a broad division of cultivated crops among those areas in and around the Indus valley on the one hand and Gujarat on the other hand, used to be recognized. In the Indus area, the cereal component was considered to be exclusively of wheat and barley while in Gujarat, rice and millets were more important.However, both rice and finger millet have now been discovered in Harappa.

- There is a range of other cultivated crops including peas, lentils, chickpeas, sesame, flax, legumes and cotton. The range suggests cotton.In Sind, cotton is usually a summer crop and such crops have generally been cultivated with the help of irrigation. This is because rainfall is extremely scanty, at about 8 inches.

- Cattle meat was the favourite animal food of the Indus people and cattle boneshave been found in large quantities at all sites that have yielded bones.

- In addition to their meat, cattle and buffaloes must have supported agricultural operations and served as draught animals. Among other things, this is suggested by their age of slaughter. At Shikarpur in Gujarat, a majority of the cattle and buffaloes lived up to the age of maturity (approximately three years) and were then killed at various stages till they reached eight years of age. Mutton was also popular and bones of sheep/goat have been found at almost all Indus sites.

- Hunting of animals was not a negligible activity; the ratio of the bones of wild animals in relation to domesticated varieties is 1:4. The animals include wild buffalo, various species of deer, wild pig, ass, jackal, rodents and hare. The remains of fish and marine molluscs are frequently found as well as.

- As for food gathering, wild rice was consumed in the Yamuna-Ganga doab although the most striking evidence comes from Surkotada in Gujarat where the overwhelming majority of identified seeds are of wild nuts, grasses and weeds.

- In general, the Indus food economy was a broad-based, risk-mitigating system – a pragmatic strategy, considering the large and concentrated population groups that had to be supported.

Artisanal Production and Trade:

(a)Artisanal Production:

- A spectacular range of artisanal production is encountered at Indus cities.Various sculptures, seals, pottery, gold jewelry, and anatomically detailed figurines interracotta, bronze, and steatite have been found at excavation sites.

- On the one hand, specialized crafts that had roots in the preceding period became more complex in terms of technological processes, and on the other hand, the combinations of raw materials being used,expanded.

- A number of gold, terracotta and stone figurines of girls in dancing poses reveal the presence of some dance form.

A bronze statuette dating around 2500 BC “dancing girl of Mohenjo Daro” - Along with the widespread urban demand for shell artefacts, semi-precious stoneand steatite beads,faience objects, and implements as also jewellery in base and precious metals. It is now reasonably clear that the Indus civilization was not, in the main, a bronze using culture. Pure copper was the dominant tradition.Additionally, there was a variety of alloys ranging from low and high grade bronzes to copper-lead and copper-nickel alloys.

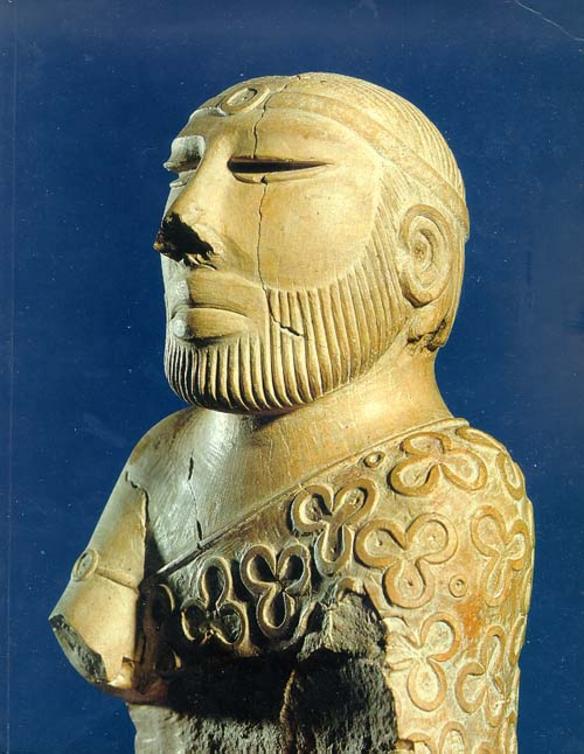

- Some of the crafted objects are quintessentially Indus, in the sense that they are neither found prior to the advent of the urban civilization nor after its collapse.Indus seals (inscribed, square or rectangular in shape,with representations of human or divine figures, animals, most notably the ‘unicorn’ along with bulls, rhinoceroses, elephants, etc. and few symbols of Indus script) for example, are rarely found in the late Harappan and post-Harappan contexts since the commercial transactions for which they were used had dramatically shrunk.Theseals were produced mostly of steatite with a loop for suspension on the reverse, and fired to obtain white surface.(The same technology was employed to decorate carnelian beads with white linear designs).The animal depicted on a majority of seals at sites of the mature period has not been clearly identified except some like bull, zebra etc. As yet, there is insufficient evidence to substantiate claims that the image had religious or cultic significance.

Indus Unicorn Seal

Humped Bull, Harappa - This is also true for the series of Indus stone statues of animals and men, of which the most famous is that of the ‘Priest King’. These appear to have had a politico-religious significance and are in a sculptural idiom that is very much within the realm of ‘High Art’. The disappearance of this stone carving tradition can be linked to the abandonment of urban centres, along with the migration and transformation of elite groups.

So called “Priest-King” in Mohenjodaro mde of soapstone

- Similarly,long barrel carnelian beads are a typical Indus luxury product, which were primarily manufactured at Chanhundaro. Their crafting demanded both skill and time; the perforation in a 6 to 13 cm length bead required between three to eight days. Evidently, the largely deurbanized scenario that followed the collapse of cities could not sustain such a specialized production.

5 inches long Carnelian Beads in Chanhudaro (one of the longest) - Many crafts “such as shell working, ceramics, and agate and glazed steatite bead making” were used in the making of necklaces, bangles, and other ornaments from all phases of Harappan sites and some of these crafts are still practised in the subcontinent today. Some make-up and toiletry items (a special kind of combs, the use of collyrium and a special three-in-one toiletry gadget) that were found in Harappan contexts still have similar counterparts in modern India.

- A harp-like instrument depicted on an Indus seal and two shell objects found at Lothal indicate the use of stringed musical instruments. The Harappans also made various toys and games, among them cubical dice (with one to six holes on the faces), which were found in sites like Mohenjo-Daro.

Miniature votive figurines or toy models from the Harappa region

- One of the most striking features of the Indus craft traditions is that they are not region-specific. Shell objects were manufactured at Nagwada and Nageshwar in Gujarat and at Chanhundaro and Mohenjodaro in Sind. Similarly, metal artefactswere produced at Lothal in Gujarat, at Harappa in the Bari doab of Punjab and atAllahadino and Mohenjodaro in Sind.

- While craft objects were manufactured at many places, the manufacturing technology could be surprisingly standardized. In the case of shell bangles, at practically all sites they had a uniform width and they were almost everywhere sawn by a saw that had a blade thickness of between 0.4 mm and 0.6mm.

- What is equally striking about the wide distribution of craft production is that, in a number of cases, manufacture depended on raw materials that were not locally available. At Mohenjodaro, shell artifacts were manufactured from the marine mollusc found along the Sind and Baluchistan coast. Similarly, there is evidence of manufacture of copper based craft items at Harappa ranging from furnaces to slag and unfinished objects, even though the city was located in a minerally poor area.

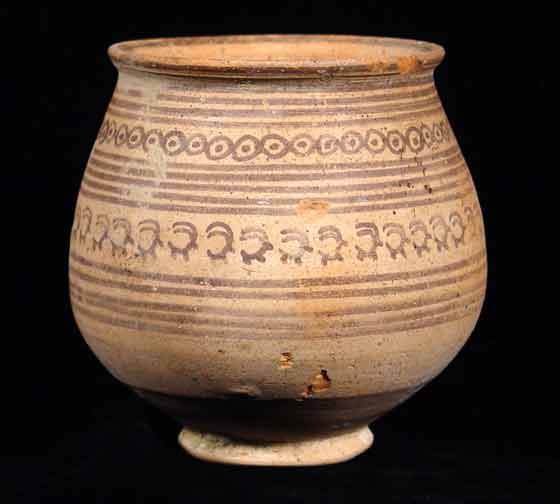

Pottery:

- The Harappan pottery is dark red and uniformly sturdy and well baked. It consists chiefly of wheel made wares both plain and painted.

- The plain pottery is more common than the painted ware. The plain ware is usually of red clay with or without a fine red slip.

- The painted pottery is of red and black colours. Several methods were used for the decoration of pottery. Geometrical patterns, circles, squares and triangles and figures of animals, birds, snakes or fish are frequent motifs found in Harappan pottery. Another favourite motive was tree pattern. Plants, trees and pipal leaves are found on pottery. A hunting scene showing two antelopes with the hunter is noticed on a pot shreds from the cemetery H.

- A jar found at Lothal depicts a scene in which two birds are seen perched on a tree each holding a fish in its beak.

- Animals depicted on the monochromatic pottery from the Indus Valley are humped bulls, pumas, birds, etc. Bulls and pumas symbolized abundance, fecundity and power.

- Sometimes they are also depicted facing a tree in a scene that may be interpreted as receiving life from a sacred tree of life. This motive derives from ancient Mesopotamia and is known from numerous ritual scenes where gods, kings, beasts and animals approach the tree of live. The tree of life in the Indus Valley civilization is a pipal tree.

- Harappan people used different types of pottery such as glazed, polychrome, incised, perforated and knobbed. The glazed Harappan pottery is the earliest example of its kind in the ancient world. Incised ware is rare and the incised decoration was confined to the bases of the pans. Perforated pottery has a large hole at the bottom and small holes all over the wall and was probably used for straining liquor. Knobbed pottery was ornamented on the outside with knobs.

Some pots were found with holes punched in the sides. Pots like this may have been used to create fermented drinks like beer - In contrary to monochromatic pottery another type of was multicolored polychrome and extremely thin and light. Polychrome pottery is rare and mainly comprised small vases decorated with geometric patterns mostly in red, black and green and less frequently in white and yellow. Examples of multicoloured pottery found in Mehrharh. The pottery is decorated with geometric patterns, fish, birds, cows, antelopes, scorpions, fantastic beasts, griffins, etc. However, instead of a whole pipal tree only as a single leaves are depicted.

Cup, Mehrgarh, 3rd millennium B.C.

Vessel, Mehrgarh, 3rd millennium B.C

(b)Trading System:

- Such craft production could survive and prosper because of a highly organized trading system. Indus people had the capacity to mobilize resources from various areas ranging from Rajasthan to Afghanistan and,considering the scale of manufacture, it is likely that there were full-time traders that helped in providing the necessary raw materials. Most of these resource-rich areas also show evidence of contact with the Indus civilization. For example, at Chalcolithic Kulli culture sites, Harappan unicorn seals and pottery have been found. Similarly, the exploitation of Rajasthan’s raw materials is underlined by Harappan pottery at some sites of the Ganeshwar-Jodhpura chacolithic complex and by the strong stylistic similarities in the copper arrowheads,spearheads and fish hooks of the two cultures.

- In addition to raw materials, other types of objects were traded. There was trade infood items as is underlined by the presence of marine cat fish at Harappa, a city that was hundreds of kilometers away from the sea. Craft items were also traded. Small manufacturing centres like Nageshwar were providing shell ladles toMohenjodaro which also received chert blades from the Rorhi hills of Sind.

- There was exchange of finished objects between the monumental cities of the Indus civilization as well. For instance, stoneware bangles – a highly siliceous ceramic body with low porosity – manufactured at Mohenjodaro have been found 570 kilometres north, at Harappa. The nature of the social process involved in this exchange is unknown but is unlikely to be a case of satisfying an economic demand,since Harappa was also producing such bangles. Possibly, the unidirectional movement of some bangles from Mohenjodaro to Harappa is related to social transactions among related status or kin groups in the two cities.

- The IVC may have been the first civilization to use wheeled transport.Theseadvances may have included bullock carts as well as boats.

- Archaeologists have discovered a massive, dredged canal and what they regard as a docking facility at the coastal city of Lothal in Gujarat state.

- There was inland trade, coastal trade, marine trade, internal trade and external trade. Many Harappan cities were located on the main trade routes. Shortughai in Afghanistan was a trade outpost.

(c)Contact with outside IVC:

- The Indus civilization had wide ranging contacts with cultures and civilizations to the northwest and west of its distribution area. Indus objects have been found innorth Afghanistan, Turkmenistan, Iran, Bahrain, Failaka and the Oman in the Persian Gulf, and Mesopotamia.

- The objects include etched carnelian and long barrel-cylinder carnelian beads, square/ rectangular Indus seals, pottery with the Indus script, ‘Indus’ motifs on local seals, ivory objects, and various terracottas.

- Externally derived objects and traits have been found at Indus sites such as seals with Mesopotamian and Persian Gulf affinities, externally derived motifs on seals and steatite/ chlorite vessels.

- At the same time, the importance that has been attached in Indus studies to the regions west of Baluchistan as the main areas from which the Indus civilization procured its raw materials, (whether it is copper from Oman or carnelian of Persian Gulf origin) is somewhat misplaced. There is an abundance of raw materials on the peripheries and within the area where Indus cities and settlements flourished. Before the advent of Indus urbanism, these raw materials were being used by the various culture that were antecedent to the Indus civilization and subsequently as well, they continued to be a part of the repertories of late/post-Harappan horizons, albeit on a reduced scale as compared to the situation during the civilizational phase. While, there may have been some raw materials involved in long distance trade, there is no reason that the Indus civilization was in any way either solely or significantly dependent on the regions to the west for such resources.

- Several coastal settlements like Sotkagen-dor, Sokhta Koh ,and Balakot (near Sonmiani) in Pakistan along with Lothal in India testify to their role as Harappan trading outposts. Shallow harbors located at the estuaries of rivers opening into the sea allowed brisk maritime trade with Mesopotamian cities.

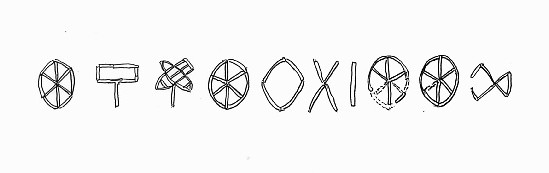

Writing System:

- Between 400 and as many as 600 distinct Indus symbols have been found on seals, small tablets, ceramic pots and more than a dozen other materials, including a“signboard” that apparently once hung over the gate of the inner citadel of the Indus city of Dholavira.

Ten Indus Signs, dubbed Dholavira Signboard - Typical Indus inscriptions are no more than four or five characters in length, most of which (aside from the Dholavira “signboard”) are tiny.

- Many have clained that these were to symbolise families, clans, gods, and religious concepts.

- Many others have claimed on occasion that the symbols were exclusively used for economic transactions, but this claim leaves unexplained the appearance of Indus symbols on many ritual objects, many of which were mass-produced in moulds. No parallels to these mass-produced inscriptions are known in any other early ancient civilizations

- The messages on the seals have proved to be too short to be decoded by a computer. Each seal has a distinctive combination of symbols. The symbols that accompany the images (Pictograph) vary from seal to seal, making it impossible to derive a meaning for the symbols from the images.

- There are more than 400 basic signs and the script is also called logo-syllabic i.e. each symbol stood for a word or syllable. It is generally written right to left but longer inscription with more than one line is written in boustrophedon style(consecutive lines starting in opposite direction).

Technology:

- The people of the Indus Civilization achieved great accuracy in measuring length,mass, and time.

- They were among the first to develop a system of uniform weights and measures. A comparison of available objects indicates large scale variation across the Indus territories.

- Harappans used weights and measures for commercial as well as building purposes. Numerous articles used as weights have been discovered. The weights proceeded in a series, first doubling from 1, 2, 4, 8 to 64 and then in decimal multiples of 16.

- Several sticks inscribed with measure marks have been discovered. Harappans were inventors of linear system of measurement with a unit equal to one angula of the Arthasastra.

- Their smallest division, which is marked on an ivory scale found in Lothal, was approximately 1.704 mm, the smallest division ever recorded on a scale of the Bronze Age.

- These chert weights were in a ratio of 5:2:1 with weights of 0.05, 0.1, 0.2, 0.5, 1, 2, 5, 10, 20, 50, 100, 200, and 500 units, with each unit weighing approximately 28 grams, similar to the English Imperial ounce or Greek uncia, and smaller objects were weighed in similar ratios with the units of 0.871. However, as in other cultures, actual weights were not uniform throughout the area. The weights and measures later used in Kautilya’s Arthashastra (4th century BCE) are the same as those used in Lothal.

- Harappans evolved some new techniques in metallurgy and produced copper, bronze, lead, and tin. The engineering skill of the Harappans was remarkable, especially in building docks.

- The people of the Indus Valley Civilization, from the early Harappan periods, had knowledge of proto-dentistry. Evidence for the drilling of human teeth in vivo (i.e., in a living person) was found in Mehrgarh.

- A touchstone bearing gold streaks was found in Banawali, which was probably used for testing the purity of gold (such a technique is still used in some parts of India)

Religious Beliefs:

- One of the most complex issues concerning ancient history is to determine past ways of thought and beliefs, especially in the case of the Indus civilization where these must be inferred from material remains, since its writing has not been satisfactorily deciphered.

- The archaeological indicators here are mainly portable objects of various kinds, figural representations and a few areas within settlements which seem to have been set apart for sacred purposes.

- There are no structures at Indus sites that can be described as temples nor are these any statues, which can be considered as images that were worshipped. In contrast to contemporary Egyptian and Mesopotamian civilizations, Indus valley lacks any monumental palaces, even though the society possessed the requisite engineering knowledge. This may suggest that religious ceremonies, if any, may have been largely confined to individual homes or open air.

- Prominent possible features of the Indus religion:

- Use of baths and water in religious practice

- Symbolic representation of the phallus (linga) and vulva (yoni)

- A Great Male God and a Mother Goddess

- Deification or veneration of animals and plants

- A few structures reflect a connection between concepts of cleansing through water relation to ritual functions. The sunken, rectangular basin known as the ‘Great Bath’ at Mohenjodaro is one such instance. The cult connection of this water using structure is evident from its method of construction which had three concentric zones around it, including streets on all four sides (making it the only free standing structure of the city), for the purpose of a ritual procession leading into it. The bathing pavements and well in the vicinity of the offering pits on Kalibangan’s citable also underline this connection.

- As for beliefs connected with fertility, it is possible that some terracotta Mohenjodaro and Harappa were related to fertility cult.

- John Marshall hypothesized the existence of a cult of Mother Goddess worship based upon excavation of several female figurines, and thought that this was a precursor of the Hindu sect of Shaktism. However the function of the female figurines in the life of Indus Valley people remains unclear. Some of stones interpreted by Marshall to be sacred phallic representations are now thought to have been used as pestles or game counters instead, while the ring stones that were thought to symbolize yoni were determined to be architectural features used to stand pillars, although the possibility of their religious symbolism cannot be eliminated.

Harappan Mother Goddess - At towns like Kalibangan and Surkotada, female figurines are practically absent. Even at Mohenjodaro, the fact that only 475 of the total number of terracotta figurines and fragments represented the female form means that fertility cult was not as common a practice as it has been made out to be. Several of the female figurines were utilized as lamps or for the burning of incense.

This stone lamp, which may show a mother-goddess, was found at Mohenjo-Daro - Fertility in relation to the male principle has also been evokfed not merely in the context on the ‘Siva-Pasupati’ seal but also with reference to the phallic stones(found at Mohenjodaro, Harappa and Dholavira) and with regard to a miniature terracotta phallic emblem set in a ovular shaped from Kalibangan.

- Marshall identified the figure as an early form of the Hindu god Shiva (or Rudra), who is associated with asceticism, yoga, and linga; regarded as a lord of animals; and often depicted as having three heads. The seal has hence come to be known as the Pashupati Seal. Many critics have raised several objections. Some has argued that the figure does not have three faces, or yogic posture, and that in Vedic literature Rudra was not a protector of wild animals. Some says: While it would be appropriate to recognize the figure as a deity, its association with the water buffalo, and its posture as one of ritual discipline, regarding it as a proto-Shivawould be going too far.

- Religious sancity was associated with particular trees and animals as well. The presence of part human-part animal characters on Indus seals and a human personage on a pipal tree, in fact, suggest a shamanistic component in Harappan religion.

- None of these features, however suggest a transregional Indus religion with cult centres and state dominated rituals, of the kind that is writ large on the architectural landscape of Bronze Age West Asia and Egypt.

Decline, Devolution and Later Harappan:

- The process of urban decline appears to have unfolded in various ways. AtMohenjodaro there was a steady deterioration, apparent in the fact that the walls of the terminal level structures are frequently thin walled, haphazardly laid out, made of unstandardized bricks. This is also true of Dholavira whose progressive impoverishment was hastened by two spells when the city was deserted.

- As urbanism crumbled, rickety, jerry-built structures and the reused stones robbed from older structures came to be commonly encountered.

- On the other hand, Kalibangan and Banawali was abandoned relatively suddenly.

- It is not one even but different kinds of events that must have led to the disappearance of urban life.

Aryan Invasion:

- The earliest formulations for urban collapse revolved around the attack of an Indo-European tribe from Central Asia called the “Aryans”.

- As evidence, a group of 37 skeletons found in various parts of Mohenjo-Daro (apparently sings of a ‘massacre’), passages in the Rig Veda referring to battles and forts, and Cemetery H Culture overlying the mature Harappan phase which was supposed to represent the conquerors.

- Since the 1950s, however serious doubts have been raised about the historicity of an Aryan invasion. Among other things, it has been demonstrated that the massacre evidence was based on very few skeletons and also skeletons belonged to a period after the city’s abandonment and none were found near the citadel. Also it was shown that marks on the skulls were caused by erosion, and not violent aggression.

- Now many scholars believe that the collapse of the Indus Civilization was caused by drought and a decline in trade with Egypt and Mesopotamia.It has also been suggested that immigration by new peoples, deforestation, floods, or changes in the course of the river may have contributed to the collapse of the IVC.

Role of river and climate change:

- Increasingly, greater attention has been paid to the question of the environment in the Indus distribution area and the role of rivers and climate in the decline of an urban culture.

- At several Indus cities such as Mohenjodaro, Chanhudaro and Lothal, there are silt debris intervening between phases of occupation and these underline the possibility of damage being caused by the inundations of swollen rivers. It has been suggested that the excess river water was a product of earthquakes, although this has not been consequence not of excessive but insufficient river water. The river in question is the Ghaggar-Hakra, often been identified with the Vedic Saraswati, which was drying up number of sites dramatically shrank in the phase that post-dates the urban one.

- The reduction in the flow of the Ghaggar-Hakra was a consequence of weekening monsoon, river diversion by techtonic events and, according to one group of scholars it was the Sutlej that abandoned its channel and began to flow westwards, while others have contended that the Yamuna was diverted from the Indus into the Ganges system.

- The Indus valley climate grew significantly cooler and drier from about 1800 BCE, linked to a general weakening of the monsoon at that time.

Shifting of Monsoon:

- Climate change in form of the easterward migration of the monsoons led to the decline of the IVC. According to this theory, the slow eastward migration of the monsoons across Asia initially allowed the civilization to develop. The monsoon-supported farming led to large agricultural surpluses, which in turn supported the development of cities.

- The IVC residents did not develop irrigation capabilities, relying mainly on the seasonal monsoons. As the monsoons kept shifting eastward, the water supply for the agricultural activities dried up. The residents then migrated towards the Ganges basin in the east, where they established smaller villages and isolated farms. The small surplus produced in these small communities did not allow development of trade, and the cities died out.

Role of impact on environment:

- The impact of the Harappans on their environment is also a factor that has been considered as contributing to the collapse of the Indus civilization.

- A possible disequilibrium between urban demand and the carrying capacity of the land, leading to a fodder requirements and fuel for firing bricks are among the explanations that have been offered.

- In the stretch that lies roughly east of Cholistan, the absence of long-term cultural roots has been highlighted. It has been suggested that since the Indus phenomenon there did not evolve through a long process but was imposed on a hunting-gathering economic context, its presence over time came to be thinly stretched and eventually, could not be sustained. But the question of the absence of a long antecedence for the civilization in the Indo-Gangetic divide and Gujarat may require modification in the context of the discovery of cultures antedating the mature Harappan phase in Kutch and Saurashtra on the one hand, and in the Hissar area of Haryana on the other. At the same time, in the period following the demise of the urban form, chalcolithic village cultures as also microlithic hunter-gatherers are encountered, an indicator that such cultures were economically sustainable in those regions. However, the highly complex system of an urban civilization, which delicately balanced different social and economic sub-system, was no longer viable.

After Collapse of Indus Urbanism (Later Harappan)

- What followed the collapse of Indus urbanism was a variety of late/post Harappan cultures –

- Cemetery H culture in Punjab and Cholistan,

- Jhukar culture of Sind: The Jhukar Phase followed the Harappa Culture around the middle of the 2nd millennium BC. It, in turn, was followed by the Jhangar Phase.Thisphase is characterized by some seals although no writing was found on it.

- Rangpur IIB and Lustrous Red Ware phases of Gujarat.

- Previously, it was also believed that the decline of the Harappan civilization led to an interruption of urban life in the Indian subcontinent. However, the Indus Valley Civilization did not disappear suddenly, and in this latter phase, a few elements of the Harappan tradition persisted to a greater or lesser degree, medicated by other cultural elements.

- Material culture classified as Late Harappan may have persisted until at least 1000–900 BCE and was partially contemporaneous with the Painted Grey Ware culture.

1900–1300 Late Harappan (Cemetery H); Ochre Coloured Pottery Localisation Era 1900–1700 Harappan 4 1700–1300 Harappan 5 1300–300 Painted Gray Ware, Northern Black Polished Ware (Iron Age) Indo-Gangetic Tradition - Recent archaeological excavations indicate that the decline of Harappa drove people eastward. After 1900 BCE, the number of sites in India increased from 218 to 853.

Cemetary H Culture:

- The Cemetery H culture developed out of the northern part of the Indus Valley Civilization around 1700 BCE, in and around western Punjab region. It was named after a cemetery found in “area H” at Harappa.

- Together with the Gandhara grave culture and the Ochre Coloured Pottery culture, it is considered as a nucleus of Vedic civilization.

- The distinguishing features of this culture include:

- The use of cremation of human remains. The bones were stored in painted pottery burial urns. This is completely different from the Indus civilization where bodies were buried in wooden coffins.

- Reddish pottery, painted in black with antelopes, peacocks etc., sun or star motifs, with different surface treatments to the earlier period.

- Expansion of settlements into the east.

- Rice became a main crop.

- Apparent breakdown of the widespread trade of the Indus civilization, with materials such as marine shells no longer used.

- Continued use of mud brick for building.

What does the end of the Indus civilization mean in relation to the character of the cultural developments that followed?

- Urban settlements, for example, did not disappear completely – Kudwala in Cholistan, Beyt Dwaraka off the coast of Gujarat and Daimabad in the upper Godavari basin are three of them. But they are relatively few, and certainly there is not city that matches the grandeur and monumentality of Mohenjodaro and Harappan cities, although baked bricks and drains are present in the Cemetery Hoccupation at Harappa while at Sanghol there was a solid mud platform on which mud houses stood.

- Writing is occasionally encountered but remains generally confined to a fewpotsherds. The same holds true for seals, which became rare, and at Daimabad and Jhukar are circular, not rectangular like the typical Indus specimens. The Dholavira specimens, on the other hand, are rectangular but without figures.

- The other indicator of a reduction in the scale of trade is the relatively sparse evidence of interregional procurement of raw materials. On the whole, one would say that elements emblematic of the urban tradition of the Indus civilization dramatically shrank and finally disappeared.

- There was no cultural cohesion or artefactual uniformity of the kind that was a hallmark of that civilization. Instead of a civilization, there were cultures, each with its own distinct regional identity.(Localisation Era).

- Not everything that is associated with the Indus civilization disappeared. A few craft traditions survived urban collapse and are found in the makeup of the late/post-Harappan mosaic. Faience (Glazed earthenware decorated with opaque colors) was one such craft and ornaments fashioned out of this synthetic stone are commonly found in the post-Harappan period.

- A similar continuity can be seen in the character of metal technology, although there was a general decrease in the use of copper. The bronzes from Daimabad in Maharashtra made by the “lost wax” process and the replication of a marine shell in copper at Rojdi in Gujarat are evidence of this and underline the continuation of the technical excellence of the Indus copper and copper alloy traditions.